NYT’s Glass Is Half Full of Half-Truths

- Submitted by: Love Knowledge

- Category: Media

(Graphic: Matt Chase)

“A glance out the window shows blue sky,” Gregg Easterbrook writes in the New York Times (5/12/16).

(Graphic: Matt Chase)

“A glance out the window shows blue sky,” Gregg Easterbrook writes in the New York Times (5/12/16).

“When Did Optimism Become Uncool?” wonders a New York Times Sunday Review piece (5/12/16) by Gregg Easterbrook. “The country is, on the whole, in the best shape it’s ever been in,” Easterbrook writes. “So what explains all the bad vibes?”

It would be easier to be optimistic if the case for optimism didn’t involve so much manipulation and misrepresentation.

Take some of Easterbrook’s major points:

- “Job growth has been strong for five years, with unemployment now below where it was for most of the 1990s, a period some extol as the ‘good old days.’”

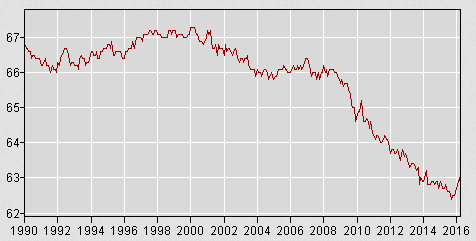

The broadest measure of employment is labor force participation—the number of people working or actively looking for work compared with the working-age population—which has been on a downward trend since the “good old days” of the 1990s. Back then, it fluctuated between 66 and 67 percent; it’s currently 62.8 percent.

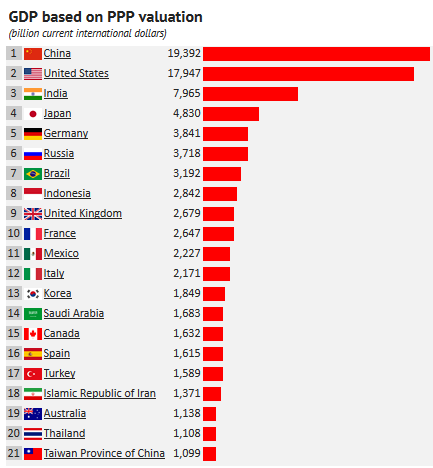

- “The American economy is No. 1 by a huge margin, larger than Nos. 2 and 3 (China and Japan) combined.”

Source: Knoema Data Atlas, based on IMF World Economic Outlook

This is based on nominal Gross Domestic Product, which expresses national output in terms of trade value, which is subject to the manipulation of currency exchange rates. When you look at GDP in terms of Purchasing Power Parity, which looks at the actual value of goods and services and is generally considered a more accurate measure of standard of living, the US does not have the largest economy in the world—China does.

- “Living standards, longevity and education levels continue to rise.”

As Easterbrook tries to explain away later on, median household income has fallen more than $4,000 since 1999; it shows little signs of returning to the peak before the housing bubble burst, which itself was below the peak reached before the dot.com bubble burst.

As for longevity, Easterbrook is no doubt aware of the disturbing finding that life expectancy among middle-aged white Americans is actually dropping, due to increases in deaths from suicide, cirrhosis of the liver and opiate overdose. Perhaps he attributes such deaths to insufficient optimism.

The percentage of Americans with bachelor’s degrees is continuing to rise, due to legitimately good news about higher rates of college degrees for women. American men, however, are graduating from college at about the same rate they did 40 years ago. High-school graduation rates for both men and women plateaued at about the same time.

US median household income peaked in 1999. Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

As I noted, Easterbrook tries to dismiss the generation-long decline in household income, probably the most basic reason for the pessimistic mood that puzzles him so:

Yes, inflation-adjusted middle-class household income peaked in 1998 and has dropped slightly since. But during the same period, federal income taxes on the middle class went down, while benefits went up. Gary Burtless of the Brookings Institution has shown that when lower taxes and higher benefits are factored in, middle-class buying power has risen 36 percent in the current generation.

What is meant here by “higher benefits” is the mostly the fact that health insurance costs much more now than it did 20 years ago—an average family’s health insurance premium went from about $7,500 in 1996 to $16,000 in 2014 (both figures in 2014 dollars). Few people would point to rampant healthcare inflation as a reason for optimism.

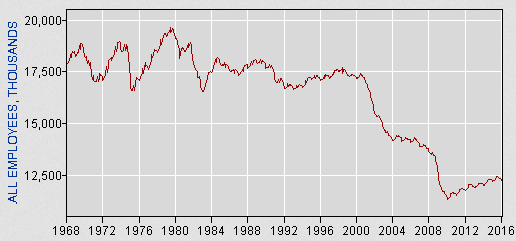

Easterbrook likewise assures us that the loss of manufacturing jobs is nothing to worry about:

Is American manufacturing in free fall, as Mr. Sanders and Mr. Trump assert? Figures from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis show industrial output a tad below an all-time record level, while nearly double the output of the Reagan presidency, another supposed golden age. It’s just that advancing technology allows more manufacturing with fewer workers—a change unrelated to foreign competition.

Actually, as Dean Baker (Beat the Press, 5/7/16) has pointed out, manufacturing jobs held fairly steady at about 17.5 million from the late 1960s until 2000, whereupon they began to plunge precipitously, to the point where they’re now less than 12.5 million. This was not because technology suddenly began advancing faster in the 21st century, but because an over-valued dollar and changes in trade rules allowed for a dramatic rise in imports without a corresponding rise in exports. In any event, replacing “foreign competition” with “advancing technology” as a reason for manufacturing job loss is unlikely to boost optimism, as it’s people—not “industrial output”—that experience pessimism.

Source: CEPR, based on BLS data

Easterbrook is particularly upset about progressive pessimism. “In recent decades, progressives drank too deeply of instant-doomsday claims. If their predictions had come true…crop failures would be causing mass starvation.” According to the UN World Food Programme, malnutrition kills more than 3 million children a year. I guess that’s not mass enough for him.

Even when Easterbrook acknowledges problems, he uses them as an excuse to beat up progressives for insufficient optimism:

Climate change, inequality and racial tension are viewed not as the next round of problems to be solved, but as proof that the United States is horrible…. Optimists understand that where the nation has faults, it’s time to roll up our sleeves and get to work.

It’s difficult to get to work, though, before the nation’s opinion makers have admitted the scope of the problem. Take climate change: The recent Paris Agreement was generally praised in US media as a landmark achievement in the effort to rein in greenhouse emissions. Yet as Bill McKibben (New York Times, 12/13/15) has noted, even if most nations stick to their commitments under the deal—an assumption that requires some, well, optimism—the result would be a temperature rise of more than 6 degrees Fahrenheit, an increase that would have catastrophic consequences. Should the reaction to that fact be “Things aren’t so bad”?

As for “racial tension,” after hundreds of years of systematic oppression, African-Americans can be forgiven by not getting overly optimistic about Easterbrook’s declaration that now is finally the time to “roll up our sleeves” and do something about it.

More than 20 years ago, FAIR’s magazine Extra! (7–8/95) published a critique of Easterbrook’s “Limbaughesque science.” His work has not improved with age.

Jim Naureckas is the editor of FAIR.org. He can be followed on Twitter: @JNaureckas.

You can send a message to the New York Times at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. (Twitter:@NYTimes). Please remember that respectful communication is the most effective.

Read more http://fair.org/home/nyts-glass-is-half-full-of-half-truths/

Related items

-

Green Party's Jill Stein: Russiagate Being Exploited to Repress Leftist Opposition

Green Party's Jill Stein: Russiagate Being Exploited to Repress Leftist Opposition

-

Media or Cult? CNN Buries a Massive Russiagate Gaffe

Media or Cult? CNN Buries a Massive Russiagate Gaffe

-

"The Occupation of the American Mind": Documentary Looks at Israel's PR War in the United States

"The Occupation of the American Mind": Documentary Looks at Israel's PR War in the United States

-

Why Isn’t the Mainstream Media Honest about US Torture?

Why Isn’t the Mainstream Media Honest about US Torture?

-

In Truth and Reconciliation, First Thing’s First—The Truth

In Truth and Reconciliation, First Thing’s First—The Truth

Comments (0)