‘They Are Incentivized to Arrest People Because It Raises Money’ - CounterSpin interview with Donna Murch on for-profit punishment

- Submitted by: Love Knowledge

- Category: Justice

(image: Muhlenberg College)

Donna Murch: “Nearly everyone who’s being arrested or incarcerated is incurring criminal justice debt. And in many states you can be stripped of your right to vote until you pay off all of your criminal justice debt. So I talk about that essentially as a modern day poll tax.”

(image: Muhlenberg College)

Donna Murch: “Nearly everyone who’s being arrested or incarcerated is incurring criminal justice debt. And in many states you can be stripped of your right to vote until you pay off all of your criminal justice debt. So I talk about that essentially as a modern day poll tax.”

Janine Jackson interviewed Donna Murch about for-profit punishment for the August 12, 2016, episode of CounterSpin. This is a lightly edited transcript. | MP3 Link

Janine Jackson: When Newt Gingrich comes out for criminal justice reform, you are right to look under the hood, to question just how deep this popular reform is intended to go. Any improvements that help real people are to be wished for, but policing and prisons are systems with deep and far-reaching roots in US life. We ought to have questions about reform that comes without an honest reckoning with the fact that some of what we call problems in the criminal justice system are not so much bugs as features.

Our next guest engages these questions in an essay called “Paying for Punishment: The New Debtors’ Prison,” which appears in the July/August issue of Boston Review. Donna Murch is associate professor of history at Rutgers University, author of Living for the City: Migration, Education and the Rise of the Black Panther Party in Oakland, California, and of the forthcoming Assata Taught Me: State Violence and Mass Incarceration, From the Black Panthers to the Movement for Black Lives. She joins us now by phone from Inwood. Welcome to CounterSpin, Donna Murch.

Donna Murch: Oh, it’s my pleasure to be here.

JJ: This piece talks about ways that the state, at various levels, extracts money from criminalized people. What does that look like? What happens?

DM: I started researching this piece after being solicited to write a piece on the criminalization of debt. And what I found out is that the two are related to each other, but this process of indebting people that have been criminalized by the state is, really, I think our most pressing problem, and really a modern form of debtors’ prison. Some people call it debtors’ prison 2.0.

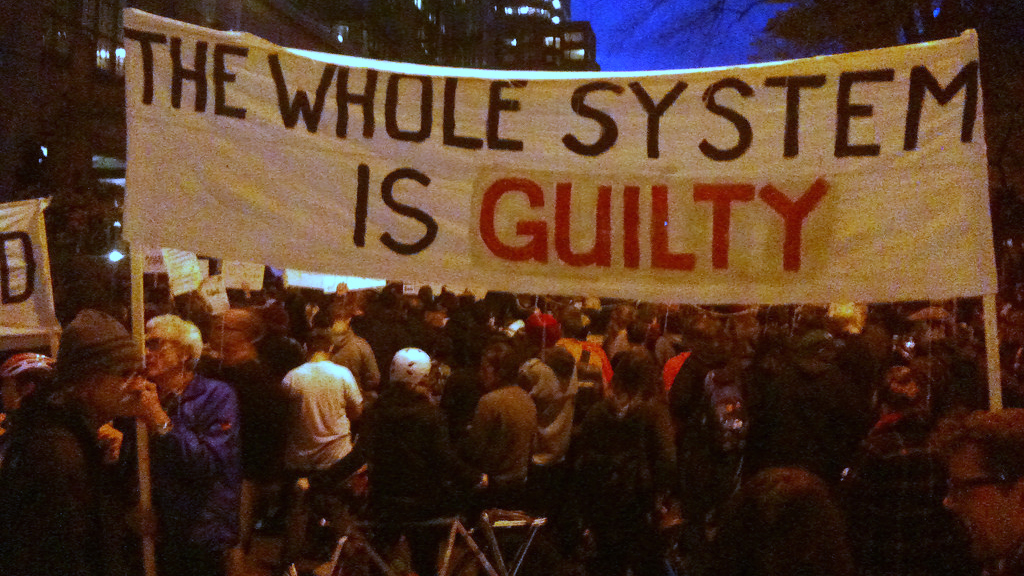

Ferguson protest banner (cc photo: Sarah Mirk)

And I think what really called attention to this was Ferguson. The protests in Ferguson are known for highlighting the militarization of police, and that was the most obvious. But through a combination of the street protests and also organizing groups like ArchCity Defenders, people discovered that Ferguson had this whole system of profiteering off of its black population.

So the black population is about 66 percent, I think; it’s about two-thirds. But a significant portion, between 20 and 25 percent, of municipal revenue came from a whole system of ticketing and criminalization that targeted the black population overwhelmingly.

And I use an example of this from Ferguson, how Michael Brown is shot in the context of Darren Wilson stopping him as he’s crossing the street— it’s really not even a street, it’s a lane inside the housing development where he lived. But the offense for which he was being accosted was walking in the street, which is illegal in Ferguson. And 95 percent of people that are given that citation are African-American.

So when Ferguson happened, I think it shined a light on something that’s a long-term problem, which is these ways that the state, especially municipalities and states—it doesn’t happen in the federal system—use the entire criminal justice system to raise revenue.

And I think that’s really important, because often when we think of incarceration, particularly in this moment since 2008, the sheer cost of it has always been seen as the potential unifying force between bipartisan and left and right consensus. But the truth is that, while people usually think about private prisons as the main way that incarceration makes money, there’re actually much more direct—and I would say people are still gathering information about this nationally—but whole systems, of charging people for criminal justice debt, legal financial obligations where if you are arrested, immediately you begin to incur criminal justice debt.

So people are charged for every step along the way of incarceration: being put in a jail, being charged jail fees. If you receive a public defender, and 80 percent of people who are prosecuted are considered indigent, so the majority, in order to receive legal representation, use these public defenders. If you choose not to go to jail, and instead the court allows you a system of electronic monitoring, many municipalities have a system called offender-funded justice in which you have to pay for the cost of wearing an electronic bracelet. And that in particular, I think, represents the future for the criminal justice system.

So it’s all these ways that they extract money from the most vulnerable populations, and they are also incentivized to arrest people because it raises money.

JJ: Isn’t there a law against it? It sounds naive, but I thought there was something in the law that acknowledged that a person who can’t pay, can’t pay.

DM: One of the things that set the United States apart from Europe was that relatively early on in the nineteenth century, it outlaws debtors’ prison. But what’s happened, I think, in the last 40 years, with the system of mass incarceration, is that it’s really just grown, you know? It’s like a monster that keeps growing in many different ways. There hasn’t been yet the constitutional challenges to this, but it’s grown up through individual municipal court practices, and then through ways that essentially private debt collectors have gamed the system.

So I think, ultimately, you have activists that are fighting this. The ACLU has played an important role in this, people challenging the practices of municipal courts. But I think that this larger campaign of punishment, in many ways… If you can incarcerate people for long periods of time for minor offenses, incarcerating them for a debt becomes much less controversial. So I think these practices ultimately will be rendered unconstitutional, but I think that they’ve been able to proliferate because of the consensus around punishment in the US.

JJ: Yeah, I was on a talk show once and a caller was defending the practice of referring to people as “illegals,” and he had hit on a technique that he liked. He said, that person who overstayed his visa, did he break the law or not? Did he break the law or not? And he just kept repeating that.

There’s an insistence that what’s being objected to is not the person’s race or their status, but simply their placement on the wrong side of “the law,” which implicitly applies equally to everyone. You know, homeless people are arrested for public urination, not for homelessness. It sort of seems like the conversation can’t move forward unless it’s taken to a different level, where we talk about how laws are made and how laws are enforced, because otherwise, this idea that someone has broken the law is kind of a thought-stopper.

DM: Yeah, I think that that’s absolutely crucial.

In many states, if you’ve been convicted of a felony, you lose the right to vote for the period you’re serving in prison, and in some states permanently, in other states for a designated period of time. Something that people know much less about is that in many states, if you have criminal justice debt, the kind that I’ve been talking about, which almost all people who are incarcerated incur…

You know, it was a real surprise to me, because I’m someone who writes about the war on drugs and mass incarceration, but I wasn’t even aware of the system of extraction until I started researching it for this article, that 41 states charge people for the cost of imprisonment, and 44 states charge people for the cost of probation. So what that means is that nearly everyone who’s being arrested or incarcerated is incurring criminal justice debt.

And in many states you can be stripped of your right to vote until you pay off all of your criminal justice debt. So I talk about that essentially as a modern day poll tax.

JJ: The self-perpetuating cycle that you write about, of debt and criminalization and incarceration, doesn’t just ruin individual lives, it also distorts our understanding of crime and of poverty, and of their relationship. It’s hard to overstate, really, how much this connection, this confluence of factors, has shaped the present landscape. And that’s one of the things that you talk about—the effect cumulatively on the racial wealth gap, for instance.

“Wanted” posters seeking return of “leased” convicts. (image: Boston Review)

DM: Yeah, I think that’s really one of the central points. In the piece, I have kind of a large historical arc. I’m a historian, and so I go back and I talk about the system of debt peonage and convict-leasing that followed the Civil War, because in many ways it’s a precedent for what we’re seeing today. And when you look at incarceration through the prism of resource extraction, it’s overwhelmingly directed at African-Americans. So, again, I think the case of Ferguson became this illustrative case. And it’s illustrative largely because people mobilized and fought back. That’s really important. We know about this story because of social protest.

JJ: Absolutely. Well, activists know that you can’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good. I seem to be making fun of this kind of left/right convergence on criminal justice reform, but we have to use the energy of the current moment to push for better. I wonder, what do you see as the hopeful glimmers at the moment, and what is the role for media?

DM: I start out my article by talking about left/right consensus, and I’m a little bit critical of it, not because I don’t think coalitions are important, but because I’m really, in a way, trying to examine the motives of some of the more conservative elements that are weighing in on incarceration and sentencing reform.

For example, expanding probation through electronic monitoring has been a way to talk about decarceration. But the problem with it is that it deeply indebts people and, as we’ve been talking about today, provides this incentive for greater criminalization.

Especially this year, with the election campaign, there’s a lot of discussion of neoliberalism, which is the idea of what happens when market practices are applied to different kinds of public goods. And this is a very concrete way that neoliberalism intersects with mass incarceration.

So it’s not just about the state rolling back social welfare and public goods. It’s about the state allowing the upward redistribution of wealth from America’s most vulnerable people, who are overwhelmingly black and brown. Looking at the recent policy platform that came out for the Movement for Black Lives, I think it’s very exciting to see the convergence of people fighting for economic redistribution and against state violence.

JJ: We’ve been speaking with Donna Murch, associate professor of history at Rutgers University. Her article “Paying for Punishment: The New Debtors’ Prison” can be found online at BostonReview.net. Donna Murch, thank you very much for joining us this week on CounterSpin.

DM: My pleasure.

Read more http://fair.org/home/they-are-incentivized-to-arrest-people-because-it-raises-money/

Related items

-

The New COINTELPRO? Meet the Activist the FBI Labeled a “Black Identity Extremist” & Jailed 5 Months

The New COINTELPRO? Meet the Activist the FBI Labeled a “Black Identity Extremist” & Jailed 5 Months

-

Trump, Corruption and the Crisis of the Global Elites

Trump, Corruption and the Crisis of the Global Elites

-

Glenn Greenwald and James Risen Debate the Trump-Russian Investigation

Glenn Greenwald and James Risen Debate the Trump-Russian Investigation

-

"They were Both Cops & Robbers": Baltimore Police Scandal Exposes Theft, Cover-Ups & Drug Peddling

"They were Both Cops & Robbers": Baltimore Police Scandal Exposes Theft, Cover-Ups & Drug Peddling

-

All Governments Lie: Truth, Deception and the Spirit of I.F. Stone

All Governments Lie: Truth, Deception and the Spirit of I.F. Stone

Comments (0)