A battle for life and water in southern Louisiana

- Submitted by: Love Knowledge

- Category: Environment

The energy at the L’eau Est La Vie camp is calm and serene, yet there’s also a palpable sense of urgency and seriousness. Through the trees and just around the corner – you can see the pipes on the ground and trenches where Energy Transfer Partners has begun construction on the Bayou Bridge pipeline. Private security drives up and down the road numerous times a day, and many people have been intimidated and targeted.

L’eau Est La Vie sits on 11 acres of private land about 2.5 hours west of New Orleans. Up until recently, it sat directly on the route of the Bayou Bridge pipeline, but Energy Transfer Partners elected to move the route just around the camp’s border. L’eau Est La Vie camp, which means “Water is Life” in French, has existed on this land since November 2017. Before moving to this site, it was a floating camp where people gathered on boats and barges to call attention to the project and the risks it brings to the Atchafalaya basin and surrounding bayous.

The purpose of the camp is to peacefully resist the pipeline, pray, inspire others to take action, and train and lead volunteers to do water monitoring to document violations by Energy Transfer Partners. In addition, the plan for the camp is to create a lasting community and space for people to learn and build the future we want to see for Louisiana and beyond.

Despite the very real and chilling realities — the intimidation, speed of construction, surveillance — the culture of the camp is positive, nurturing and replenishing. Whether it’s the beautiful budding garden that’s been planted, the colorful bouquet of flowers that sits on the table in the kitchen area, or the gorgeous art that lines the warehouse space — it is a hopeful, joyful place. The camp cat, “Puddles,” walks around greeting visitors as everyone works hard to complete projects, like building platforms for more tents as well as more permanent structures, that keep the camp running.

Last week, I joined together with people from across Louisiana and beyond to go door-to-door on a canvassing caravan, talking with communities along the pipeline route about the risks of the project and what can be done to stop it. Our group of canvassers was joined by the Black Hawk Revelators — a 7-person brass band who played in the streets as we walked around.

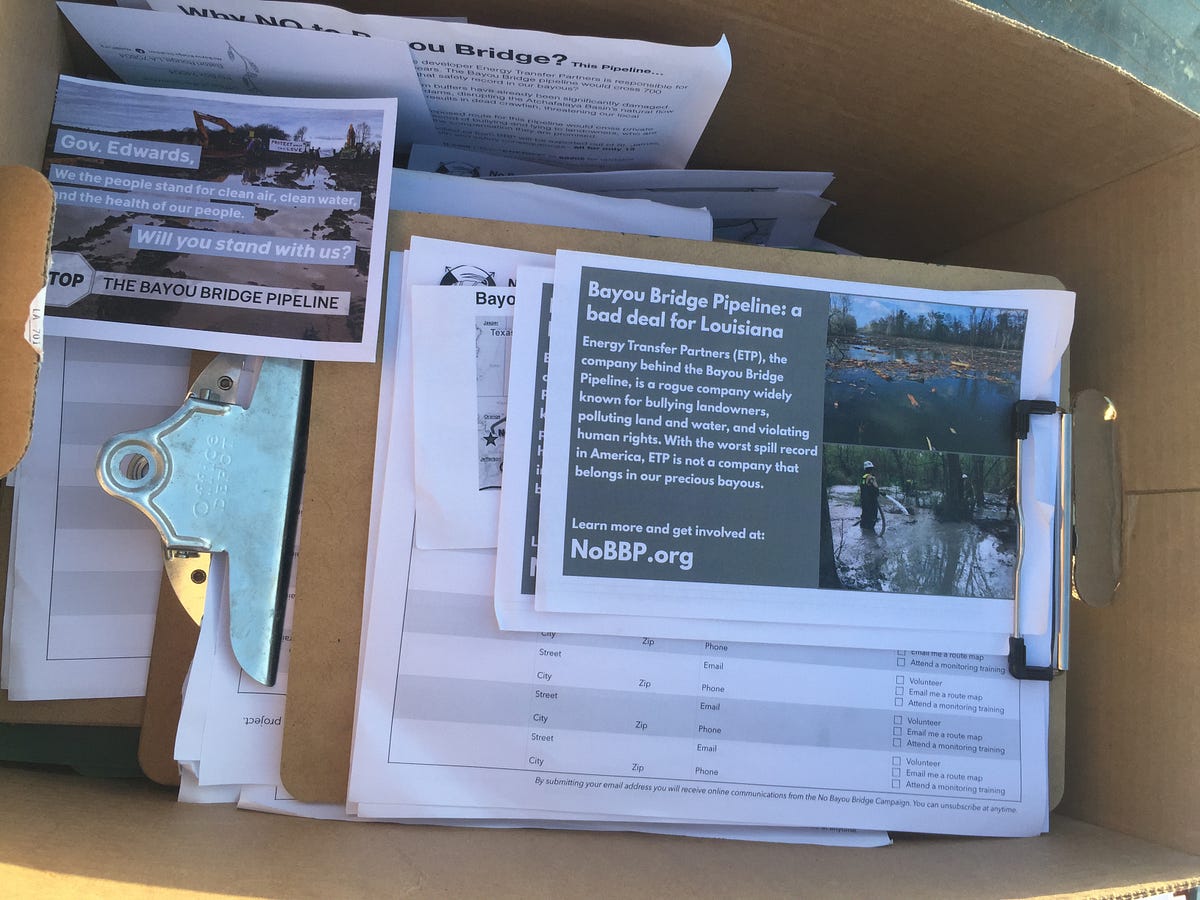

On the first day of the caravan, we departed from camp early and headed to Lake Charles where the pipeline begins. With clipboards loaded with flyers, stamped postcards to Governor Edwards, and sign-up sheets, we broke off in pairs down long streets with no sidewalks to let people know about the project and share ways to get involved.

I had many long conversations with community members, most of whom had never heard about the project. Sadly, many of them had come to expect projects like this in Louisiana which has been overrun with oil and gas for decades. Nearly everyone I spoke with was concerned about the project and signed a postcard to the Governor with a note about their concerns.

Some of the messages read: “we want clean water,” “let us live” and “please stop the pipeline.” We spoke with former employees of the industry who knew first hand what the risks are and how careless these companies are when it comes to leaks, spills, and permit violations.

While driving along the 163-mile pipeline route, the beauty of the landscape was breathtaking — green grasses, bright blue sky, and some of the warmest, welcoming people I’ve met. As we moved from Lake Charles, to Jennings, St. Martinville, Donaldsonville and St. James, the neighborhoods differed greatly in terms of race, income, and age but some things remained constant.

Everywhere I went, the role of water, industry, and flooding is omnipotent. The Bayou Bridge pipeline would cross 700 waterways, and I can understand how — rivers, bayous, and water are everywhere. They are the literal and cultural foundation in south Louisiana. This month marks the beginning of crawfish season, which means crawfish boils and economic opportunity for local fishermen. At nearly every bayou or river, I saw someone fishing, boating, hunting or enjoying a picnic with their family.

Bayou Teche in St. Martinville, Louisiana a few miles north from where the pipeline would cross.

A related constant presence is the fear of what this rising water can and has done to communities. For nearly an hour, we drove alongside a levee and flood wall, and even during the less-wet month of March, there were light-up traffic signs along the road saying “Caution: Water on Road.” Seeing homes next to the river, I found myself thinking, “I hope those cinder block stilts are high enough to weather the next storm.” The legacy of Hurricane Katrina and more recent disasters, along with the rapid loss of land due to climate change and rising sea levels, are ever present for people living in southwest Louisiana.

Recent studies show that glacial melting is accelerating in Antarctica and Greenland, driving sea level rise on the Gulf Coast. According to the United States Geological Survey, a football field’s worth of wetlands vanishes every 100 minutes — one of the highest rates on the planet which makes communities even more vulnerable to major storms.

Lastly, industry and the role it plays is impossible to ignore. Upon arriving at St. James where the pipeline ends, I saw industrial facilities bigger than most city skylines. The plants are so massive and invasive, not even the roads are spared. We drove under and through pipeline labyrinths that connect from cargo ships coming down the Mississippi directly to massive industrial plants.

118 storage containers where the oil from Bayou Bridge would be stored. St. James, Louisiana

In a matter of minutes, we passed an ammonia plant, 118 oil storage tanks where Bayou Bridge oil will be stored, and other petrochemical plants that light up the sky orange with their fluorescent lights and flares. The economy and jobs in Louisiana revolve around these dirty industries — yet while Louisiana has opened itself up to dirty industries with open arms, it is the second poorest state in the country. The Bayou Bridge pipeline would only create 12 permanent jobs.

The campaign against the Bayou Bridge pipeline is not new. Resistance began as far back as 2016 with solidarity actions in Louisiana during the historic fight against the Dakota Access pipeline. Bayou Bridge was approved by the U.S. Army Corp of Engineers, Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality, and the Louisiana Department of Natural Resources in December, although it received little national attention at the time. The project was approved without an Environmental Impact Statement — a process required for most pipelines — and much of the focus of the #NoBBP campaign has been to urge the Governor to call for an environmental review.

Photo from On March 26 action which shut down construction of the Bayou Bridge Pipeline. Photo Credit: L’eau Est La Vie Camp

While actions at the camp and efforts to target the Governor continue, much of the fight to stop the pipeline lives in the courtroom. In January, Earthjustice filed a lawsuit against the Army Corps of Engineers for acting “arbitrarily and capriciously” in issuing a permit for the Bayou Bridge pipeline. On February 24, a U.S. District Judge granted a temporary injunction to prevent irreparable harm to the Atchafalaya basin — an environmentally sensitive National Heritage Area — until the lawsuit could be heard. While that temporary injunction was reversed, the lawsuit continues and the hearing on the final injunction will happen in May.

Meanwhile, Energy Transfer Partners (ETP) — the same company behind the Dakota Access pipeline — continues to have the worst safety record of any pipeline company in the nation. In the first 11 weeks of 2018, ETP received 36 violations and $12.8 million in proposed fines. Recent accidents in Ohio and Pennsylvania show how careless this company is — and that their operations anywhere are inherently dangerous.

I’m grateful to all the local organizers and volunteers who are working every day to stop this pipeline — they deserve all of our appreciation. To win this fight, more attention and pressure on Governor Edwards is needed. The organizers on the ground also need financial support to keep the camp running. To get involved, visit nobbp.org and make a donation to the camp here.

Resisting Bayou Bridge is bigger than stopping one pipeline — it’s about challenging an industry that’s endangering the communities of Louisiana and the climate. We know we can do better, and we must.

Map of caravan:

Read more http://350.org/a-battle-for-life-and-water-in-southern-louisiana/

Comments (0)